As Genesis approaches its 10th anniversary, it’s a pivotal moment to reflect on the accomplishments of the past decade while setting the stage for the next. This milestone also marks the perfect time to challenge one of the world’s premier motorsports disciplines—endurance racing. High-performance technology is a crucial component of what is expected from a premium brand, and motorsport is where this technology is truly tested.

Building a high-performance brand reputation takes more than selling high-output models—it requires consistent and active involvement in racing. This is why so many premium brands participate in various motorsports disciplines. Genesis has chosen to make its debut in the World Endurance Championship (WEC), the pinnacle of circuit racing epitomized by the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

Endurance racing is a form of motorsport where vehicles are tested for their durability by running long distances over extended periods. Unlike most circuit races, which rarely exceed two hours, endurance races last a minimum of three hours and can stretch to 24 hours. Teams typically consist of 2–4 drivers who take turns piloting a single car. Notable examples include the 24 Hours of Le Mans in Europe and the 24 Hours of Daytona in the United States, both of which feature a mix of prototypes and GT race cars. Other renowned events include Belgium’s Spa 24 Hours, which focuses on GT cars, and Germany’s Nürburgring 24 Hours, featuring a variety of GT and production-based touring cars.

Endurance racing dates back to the early 20th century, during the dawn of motorsport. The world’s first 24-hour race took place in 1905 at a one-mile oval track in Columbus, Ohio. The first endurance race on a circuit was held two years later in 1907 at Brooklands in the UK. Early endurance races in the 1920s and 1930s featured road-going sports cars. After World War II, purpose-built race cars emerged, significantly raising performance levels. The introduction of sports prototype regulations in the 1950s and 1960s solidified endurance racing’s shift toward dedicated race cars.

Endurance racing has evolved around two iconic events: Europe’s 24 Hours of Le Mans and North America’s 24 Hours of Daytona. While numerous endurance races have come and gone, none have surpassed the prestige and difficulty of these two. Together, they have written countless legendary stories thanks to their rich history, immense challenges, and enduring popularity. The Triple Crown of Endurance Racing consists of victories at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, the 24 Hours of Daytona, and the 12 Hours of Sebring. Only 12 drivers, including legends like Jacky Ickx and Timo Bernhard, have achieved this pinnacle of endurance racing.

One famous story from the Triple Crown era involves Ken Miles, portrayed by Christian Bale in the movie Ford v Ferrari. In 1966, Miles was poised to win the 24 Hours of Le Mans and complete the Triple Crown. However, a team order to slow down for a synchronized finish with Ford’s other cars cost him the victory. While this created a historic photo finish for Ford, it denied Miles a place in the history books. The movie Ford v Ferrari tells the story of Ford’s determination to defeat Ferrari at Le Mans by developing the legendary GT40 race car.

The Circuit de la Sarthe, where the 24 Hours of Le Mans takes place, is located in northwestern France. This region is one of motorsport’s birthplaces. The race is organized by the Automobile Club de l'Ouest (ACO), a historic body established in 1906 that hosted the first-ever French Grand Prix. In 1923, the inaugural 24 Hours of Le Mans used public roads between villages—a tradition still reflected in today’s 13.626-km track, which combines public roads with the Bugatti Circuit.

Even during times when global endurance championships faded, the 24 Hours of Le Mans thrived. Since its inception, the race has only been canceled twice: during France’s 1936 general strike and World War II (1939–1945). Not even the global COVID-19 pandemic could stop the race’s fiery momentum.

The 24 Hours of Daytona is held in Florida at the start of the year, typically in late January or early February. Its winter scheduling aligns with motorsport’s off-season, making it a symbolic start to the track racing calendar. Daytona serves as the opening round of the IMSA Michelin Endurance Cup, followed by the 12 Hours of Sebring.

The Daytona International Speedway, located in Daytona Beach, Florida, is known for its large oval configuration. While the oval measures 4.023 km per lap, the track is modified for endurance racing into a 6-km road course. This layout incorporates high-speed banking with traditional circuit sections, creating a uniquely challenging course. Endurance racing at Daytona began in 1962 with a three-hour race, expanded to a 2,000-km event in 1964, and eventually established its current 24-hour format in 1966.

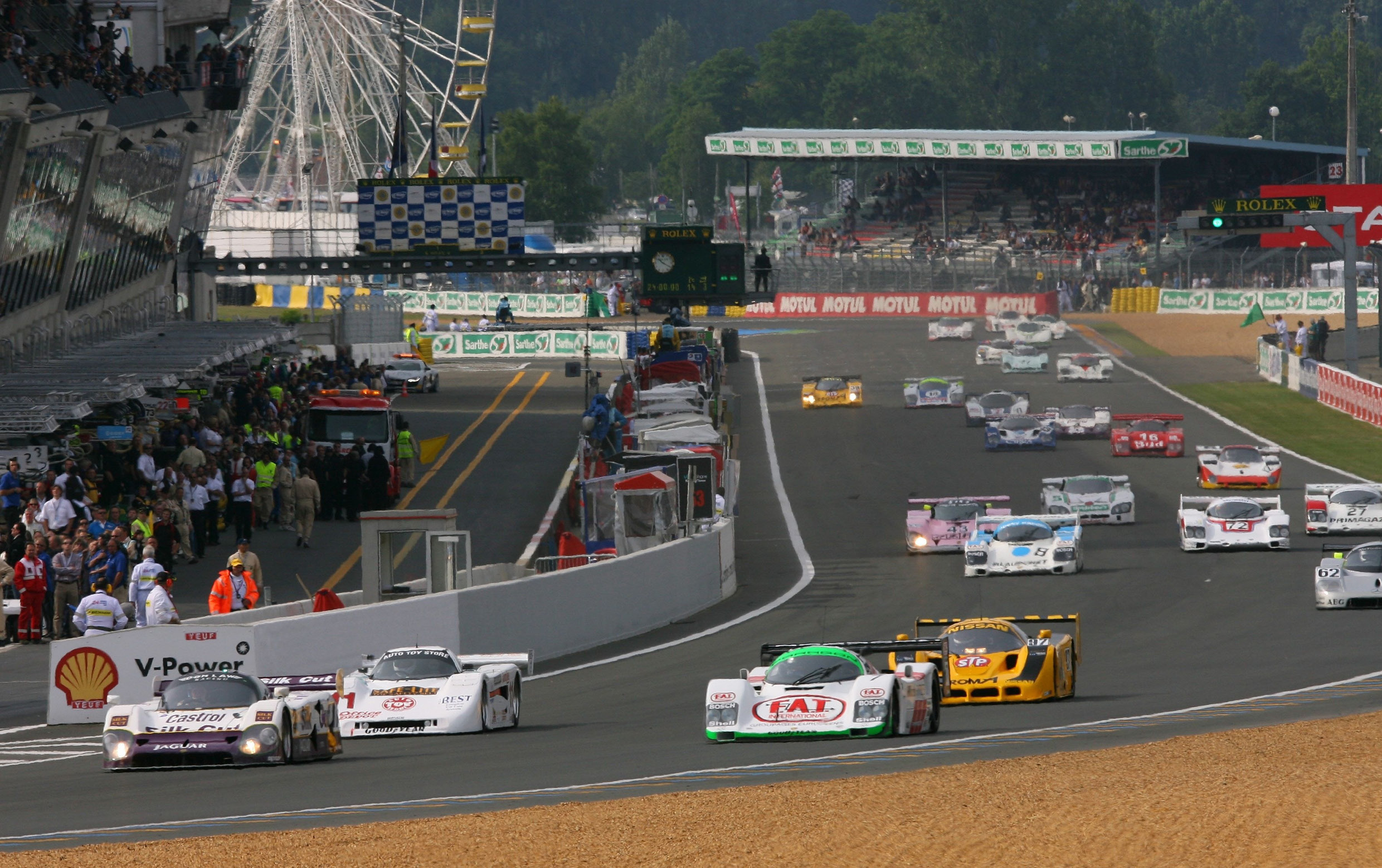

The 1980s are remembered as the golden age of endurance racing, marked by the dominance of Group C race cars. With minimal regulations encouraging widespread participation, Group C* rivaled the popularity of Formula 1. Porsche began cementing its reputation in endurance racing during this time, even selling race cars to private teams. The dominance of Porsche was so pronounced that, at the 1986 24 Hours of Le Mans, 9 out of the top 10 finishers were Porsches.

However, the domination of a single manufacturer diminished the excitement of the races. Additionally, the lack of regulatory restrictions led to intense competition and skyrocketing development costs. Contrary to its original intent, this environment discouraged new manufacturers from joining, ultimately leading to the decline of Group C. As Group C faded, Le Mans saw a significant drop in entries. To sustain its legacy, the race incorporated cars from the American IMSA series and introduced a new LM-GT (Le Mans GT) class.

*Group C was a motorsport class established by the FIA in 1982, considered the top tier of sports car racing above Group A (touring cars) and Group B (GT cars), where cars were purely prototype designs with no requirement for production-based versions and virtually no limitations on engine type or displacement, leading to a highly competitive era of technological development among manufacturers until its end in 1993.

The World Endurance Championship (WEC) was established in 2012, succeeding the World Sportscar Championship (WSC), which ended in 1992. The introduction of LMP1 (Le Mans Prototype 1) regulations brought hybrid race cars to the forefront, driven by growing environmental concerns. However, the complexity of hybrid systems, combined with rising costs, created barriers for new teams. By the time Audi and Porsche withdrew, Toyota was left as the sole competitor in the LMP1 class.

In response, WEC underwent significant changes to ensure its survival. Starting in 2021, the costly LMP1 regulations were replaced with the Le Mans Hypercar (LMH) class, which focused on cost reduction. While only Toyota, Glickenhaus, and Alpine participated in the LMH class in its inaugural year, interest quickly grew. By 2024, heavyweights like Porsche, Ferrari, Peugeot, and Vanwall joined the grid, revitalizing the series.

America’s IMSA series embraced the hypercar concept by introducing the LMDh (Le Mans Daytona hybrid) regulations, enabling greater collaboration between IMSA and WEC. Unlike the diesel engines and expensive LMP1 hybrids that once dominated Le Mans, LMDh emphasizes practicality and cost-efficiency. This approach has attracted brands such as Ferrari, Porsche, BMW, Cadillac, Lamborghini, and Toyota, creating a vibrant ecosystem that provides an ideal stage for premium brands like Genesis to make their mark.

Until recently, IMSA’s top class followed the DPi (Daytona Prototype International) regulations, which differed entirely from WEC’s framework. When Le Mans introduced the LMH concept to address LMP1’s issues, IMSA adopted the idea but further reduced costs by standardizing major components through LMDh regulations.

Unlike LMH, which allows complete design freedom, LMDh reduces costs by limiting choices. While an LMP1 season once cost around €100 million, LMH reduced this by 75%, and LMDh lowered costs even further. Additionally, both WEC and IMSA series allow crossover participation, making LMDh particularly appealing.

For LMDh, teams select carbon chassis from one of four suppliers—Oreca, Dallara, Multimatic, or Ligier. Other standardized components include integrated motor-generator unit(MGU) supplied by Bosch, batteries from Williams Advanced Engineering, and gearboxes from Xtrac. While this limits design freedom, it accelerates development and reduces operational costs during the season.

LMH and LMDh vehicles share nearly identical dimensions, with both featuring a 2-meter width and a 3.15-meter wheelbase. LMDh cars are slightly longer at 5.1 meters compared to LMH’s 5 meters. LMH allows original chassis design, while LMDh mandates using one of four pre-selected suppliers. Engine design is relatively flexible for both classes, provided it’s a four-stroke gasoline engine, whether custom-built or derived from production models. Combined engine and motor output is capped at 500 kW (approximately 670 horsepower).

However, LMH and LMDh differ significantly in hybrid assist systems. LMH vehicles can use motor-driven front wheels for temporary all-wheel drive, while LMDh integrates the motor with the gearbox, driving only the rear wheels. Additionally, hybrid assist in LMDh is restricted to higher speeds, with activation thresholds determined by Balance of Performance (BoP) regulations.

BoP is a mechanism that limits engine output, vehicle weight, and energy usage per stint to balance performance across different cars. Adjustments are based on detailed specifications recorded during certification and past race results.

Despite BoP efforts, performance differences between LMH and LMDh persist. For example, LMH vehicles offer up to 200 kW (272 horsepower) of motor assist, while LMDh is limited to 50 kW (68 horsepower). Though qualifying results at Le Mans have shown minimal differences, LMH cars have demonstrated an edge in long-distance racing due to their more robust hybrid systems.

At the 2024 Le Mans 24 Hours, the LMH-class Ferrari 499P, the reigning champion, weighed 1,053 kg with 688 horsepower and a stint energy limit of 905 MJ. In comparison, the LMDh-class Porsche 963 was lighter at 1,037 kg and produced 690 horsepower with a stint energy limit of 904MJ, while the Cadillac V-Series.R weighed 1,030 kg with 702 horsepower. Despite these figures, the Ferrari 499P claimed its second consecutive victory at Le Mans. Meanwhile, Toyota dominated the WEC season, and Porsche claimed the IMSA championship.

While LMH offers advantages at Le Mans, manufacturers targeting the U.S. market often favor LMDh. Even Porsche, with its storied Le Mans history, opted for LMDh over LMH that succeeded LMP1, surprising many.

LMH models competing at Le Mans and in the WEC include the Ferrari 499P, Toyota GR010 Hybrid, Peugeot 9X8, and Aston Martin Valkyrie AMR-LMH. Meanwhile, LMDh models like the Porsche 963, BMW M Hybrid V8, Alpine A424, Acura ARX-06, Cadillac V-Series.R, and Lamborghini SC63 compete in IMSA’s Grand Touring Prototype (GTP) class and are also eligible for Le Mans.

Although many LMDh cars have expanded into WEC and Le Mans, no LMH car has yet competed in IMSA or the Daytona 24 Hours. Aston Martin’s Valkyrie AMR-LMH, set to debut in both WEC and IMSA in 2025, will mark the first instance of such crossover participation.

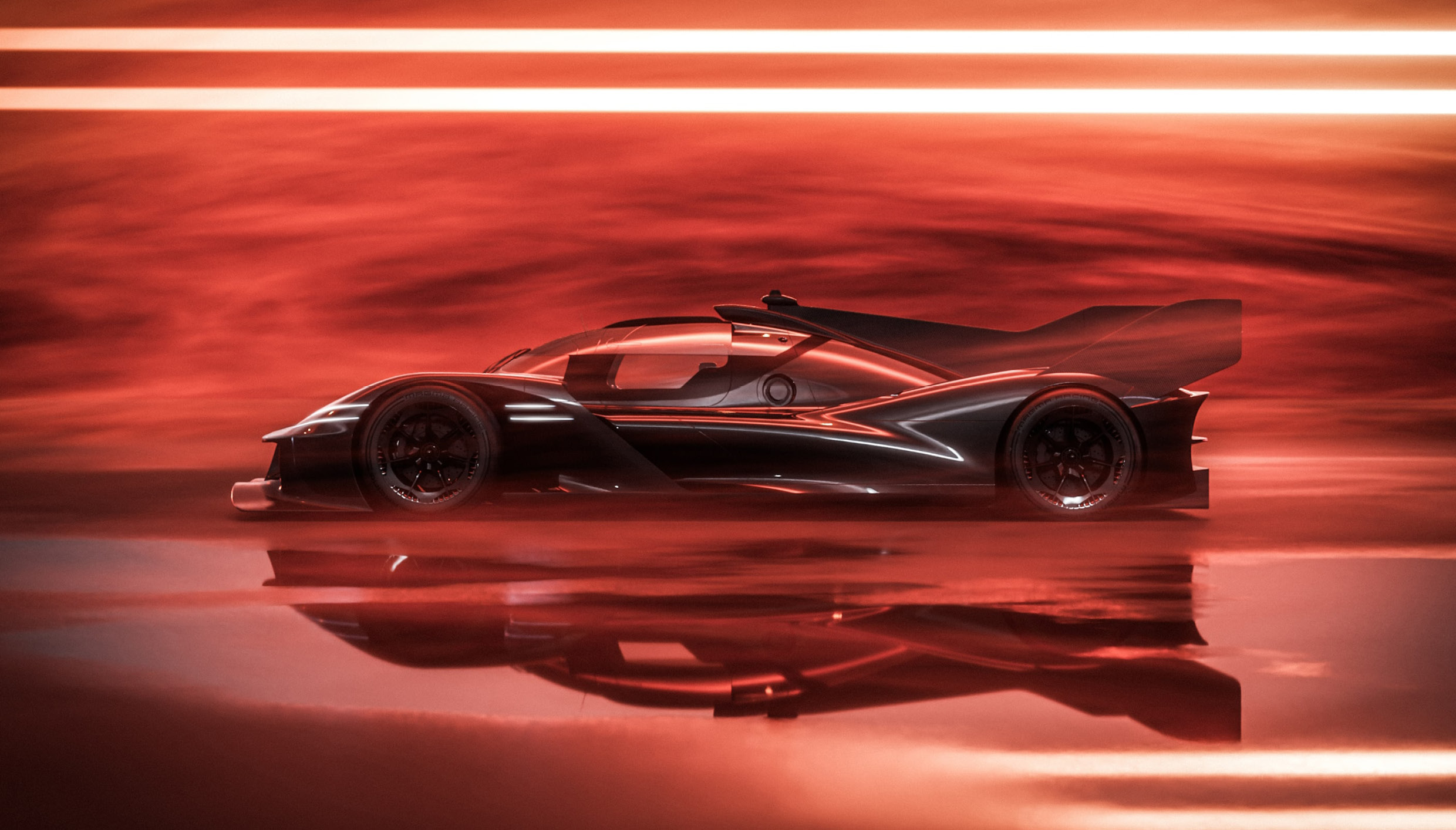

Genesis, which has only just made its foray into motorsports, unveiled a wealth of information during the Genesis Motorsport Premiere event on December 4, 2024, in Dubai, UAE. The team is named Genesis Magma Racing and plans to debut with two hypercars in the 2026 World Endurance Championship (WEC), followed by an entry into the American IMSA series in 2027. Cyril Abiteboul, President of Hyundai Motorsport GmbH, will serve as Team Principal for Genesis Magma Racing.

“The official launch of Genesis Magma Racing is a momentous occasion,” said Cyril Abiteboul, President of Hyundai Motorsport GmbH and Team Principal of Genesis Magma Racing. “As the backbone of Hyundai Motor Group’s global motorsport activities, Hyundai Motorsport will play a vital role in this latest ambitious program. We are elevating our circuit racing expertise to a whole new level as we prepare to compete in some of the world’s most challenging series.” Endurance racing is an entirely different level of motorsport compared to the TCR (Touring Car Racing) in which Hyundai Motor Group has previously excelled. Genesis will face direct competition with heavyweights like Porsche, Ferrari, BMW, Toyota, and Cadillac.

At the Genesis Motorsport Premiere, the team revealed a 1:2 scale model of the GMR-001 hypercar, offering hints about the still-developing race car. While functional priorities might lead to design changes during development, signature Genesis elements such as the two-line lamps and the sleek parabolic line are expected to remain intact. For the LMDh chassis, Genesis has partnered with French supplier Oreca, one of four approved manufacturers.

Genesis also announced two drivers who will form the backbone of its lineup: André Lotterer and Luís Felipe ‘Pipo’ Derani. André Lotterer is a veteran German driver with extensive experience across F1, Formula E, and GT racing. He has won the 24 Hours of Le Mans three times with Audi and has two WEC championship titles.

Luís Derani, from Brazil, is a standout in the IMSA SportsCar Championship, having won titles in 2021 and 2023 with Cadillac. He also achieved a rare double victory at the Daytona 24 Hours and Sebring 12 Hours in 2016 and has competed in the WEC Hypercar and LMP2 classes.

Genesis Magma Racing plans to make its official WEC debut in 2026. To prepare, the team has entered a strategic partnership with French team IDEC Sport, known for its endurance racing expertise. IDEC Sport, which was founded in 2015 and won the 2019 European Le Mans Series (ELMS) championship, will support Genesis by training drivers, engineers, technicians, and mechanics.

Genesis Magma Racing will compete in the European Le Mans Series (ELMS) next year with two LMP2 cars in collaboration with IDEC Sport. Team Principal Cyril Abiteboul expressed confidence in their partnerships with Oreca and IDEC Sport, both of which have established strong reputations in endurance racing. According to Abiteboul, André Lotterer and Luís Derani will focus on testing and development this year to prepare for Genesis’s 2026 WEC debut. At the same time, the team is working to nurture talented drivers such as Logan Sargeant, Jamie Chadwick, and Mathys Jaubert, aiming to integrate them into the IDEC Sport team for the 2025 European Le Mans Series.

American driver Logan Sargeant, who competed in F1 with Williams Racing over the past two years, has recently expanded his career into endurance racing. Jamie Chadwick, a British driver, is a standout in women’s motorsport, holding the record for the most wins and championship titles in the W Series. Meanwhile, 19-year-old French driver Mathys Jaubert is a rising star with limited experience outside the Porsche Carrera Cup but is highly regarded for his potential and promise.

One of the two LMP2 race cars that IDEC Sport will field in this year’s European Le Mans Series (ELMS) will represent Genesis Magma Racing, with the three drivers—Logan Sargeant, Jamie Chadwick, and Mathys Jaubert—sharing driving duties. However, this does not guarantee their inclusion in the 2026 WEC lineup, as they remain potential candidates at this stage. With two race cars planned for the WEC debut, Genesis will need at least six skilled and experienced drivers, requiring a rigorous and lengthy selection process.

Hyundai Motorsport GmbH will manage the Genesis Magma Racing team as it enters the WEC, but for the 2027 IMSA Championship campaign, the team plans to collaborate with a seasoned local external partner. Cyril Abiteboul, Team Principal, emphasized the importance of having IMSA-specific experience and noted that the team is still evaluating potential partners for this endeavor. As Genesis marks its 10th anniversary, the brand is embarking on an ambitious new chapter, tackling the extreme challenges of endurance racing. Many are closely watching Genesis as it ventures into this thrilling and demanding motorsport arena.

By Su-jin Lee

Soo-jin Lee’s love for cars started in 1991 when he wrote letters to Korea’s new Car Vision magazine. That connection sparked a career in automotive journalism. He’s worked as an editor and on the editorial board for